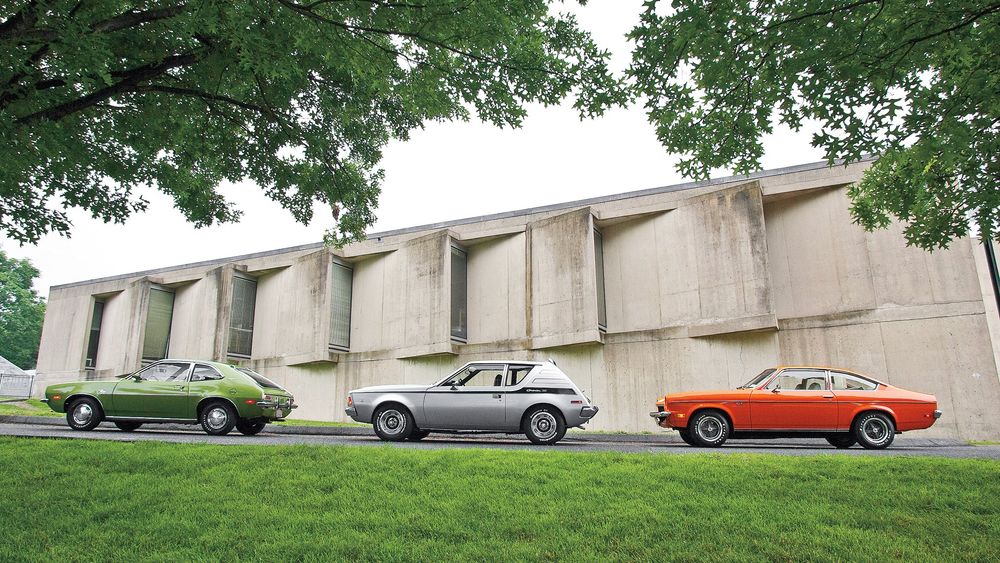

Small Blunders: 1971 AMC Gremlin X, 1973 Chevrolet Vega GT, and 1972 Ford Pinto

A loving look back at America’s second attempt to rain on the imports’ parade.

[This story originally appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of MotorTrend Classic] A big, nasty storm struck the American automotive market in 1959. It washed some 615,131 imported cars ashore, breaching 10 percent of the automotive market for the first time in history. The nation responded by hastily building seawalls bricked with Corvairs, Falcons, and Valiants. These smaller, less-profitable cars successfully stemmed the tide of quirky European and even quirkier Japanese cars.

Sighs of relief were heaved, and before long the relentless march back up in size and feature content resumed. As these Americans grew fatter and happier, the skies darkened again. Those oddball foreigners had been strengthening their dealer networks, and one in particular,Volkswagen, was quietly building a reputation for high quality and trouble-free operation. By 1968, the imports were again spilling over that 10-percent levee, prompting another round of civil engineering from Detroit. But this time, it was going to be different—or so we fervently believed:

“The Gremlin is something very near a true metropolitan commuter car…a head-on confrontation with Volks…one of the engineering/design triumphs of 1970.”—MotorTrend, March 1970 “The Vega 2300 is perhaps new enough to restructure the entire small-car market. [It] will probably be an instant success with the buying public.”—MT, August 1970 “Ford’s subcompact is definitely more European…the U.S.’ most “un-American” car ever.”—MT, December 1970

Forgive us, we had been drinking the Kool-Aid since shortly after GM chairman James Roche announced, in October 1968, that within two years the General would introduce a 2000-pound VW-priced subcompact with engineering so advanced it would stem the tide of small imported cars. His announcement sent the competition scurrying toward their drawing boards as well. (Okay, Chrysler scurried to the telephone and ordered a supply of Hillman Avengers and Mitsubishi Galants to be rebadged as Plymouth Crickets and Dodge Colts.) The compressed development time (and the memory of GM’s Corvair experience) steered all three domestics in the direction of tried-and-true front-engine, live-axle, rear-drive designs.

Among the domestics, American Motors arguably had the most cred in the small-car biz, its 1950 Nash Rambler having established the mainstream compact segment a decade before the Big Three dove in. AMC also had the tightest budget, so the company leveraged its $40-million investment in the 1970 Hornet compact by slicing out a foot of wheelbase and guillotining the rear overhang. Tooling cost just $6 million, and the design (previewed on the 1968 AMX GT concept) was fresh and controversial—jarring to older folks and hence doubly appealing to younger target buyers.

Introduced fittingly on April 1, 1970, the Gremlin beat the Vega and Pinto to market by over five months and captured the cover of the April 6 issue of Newsweek. For $1879 ($40 more than the VW), you got a stripped two-seater with fixed rear glass (only 872 of these were built in 1970); $80 more bought the four-seat glass-hatch version and still ranked Gremlin as America’s cheapest domestic. Initial engine choices included two inline-sixes that out-powered the imports with 128 and 145 horses (and also drank more fuel). A 304-cube V-8 arrived in 1972, but a 2.0-liter four-cylinder purchased from VW/Audi wasn’t available until the last two model years (’77-’78). Ancient manual transmissions didn’t have synchronizers on first gear. The shape and length were Beetlesque, but the Gremlin measured 7.3 inches lower, 9.6 inches wider, and 950 pounds heavier. That long engine also cramped the interior.

Ford split the difference in investment between penurious AMC and profligate GM, designing an all-new body on a miniaturized conventional coil-front/ leaf-spring rear suspension, then imported tried-and-true drivelines from its Euro subsidiaries. The base 75-horsepower, 1.6-liter OHV Kent engine came from England’s Ford Cortina and the optional 100-horsepower, 2.0-liter SOHC four originated in Germany’s Ford Taunus. Gearboxes and steering racks also came from Europe. Of the three domestics, the Pinto measures closest to the VW in size and weight, riding on a half-inch-shorter wheelbase, it stretches 4.4 inches longer, 8.4 inches wider, 9.0 inches lower, and just 158 pounds heavier.

Packaging is impressive, with a roomier if low-cushioned back seat, loads more shoulder room, and just 1.3 inch less front headroom. Hatchback Runabout and station-wagon models joined the two-door sedan in 1972. Innovations included an electrostatic painting process that helped paint find its way around corners and into recesses and optional floating-caliper front disc brakes (a claimed first for the domestics) that helped rank the Pinto tops among all American cars in a 1971 government braking test. The caliper design simplified maintenance as did many other features, which Ford touted to lure penny-pinching do-it-yourself owners. A DIY manual and two tool kits were available for shade-tree mechanics. A special key even doubled as a screwdriver and spark-plug gapper.

GM spent the most time (three years) and money ($200 million) readying its high-tech XP-887 mini, and its gestation was fraught with intrigue. The Chevy and Pontiac engineering organizations had been working on small-car designs, but Ed Cole (father of the Small Block and Corvair) had the central operating staff working on a mini of his own. When all were presented to management in 1967, Cole’s prestige and forceful salesmanship won the Vega approval.

His design was foisted on a reluctant Chevrolet division, which then had to cope with many gross underestimates of cost, weight, and structural design. To wit: The first prototype reportedly survived only eight miles of durability testing before the front end broke off, requiring the first 20 of approximately 200 pounds that would eventually be added to the original 2000-pound design just to make it viable.

Cole had also fallen in love with a new die-cast engine block. With proper heat-treating, Reynolds Aluminum 390 alloy (16-18-percent silicon) would tolerate the wear of an iron-coated piston without pricey liners. The feathery engine should permit further lightening of the suspension and structure in theory. In practice, the tall, cast-iron SOHC cylinder head fitted to withstand the combustion pressures of the undersquare design outweighed the block and caused the dressed 2.3-liter engine to weigh more than the Pinto’s 2.0-liter iron mill (or Chevy division’s rejected oversquare crossflow hemi four). It was also way more expensive.

The long-stroke and large displacement made this engine a shaker, so the engine mounts were softened. Early carburetors rattled themselves apart, causing dangerous fuel leaks or backfires. A recall of 130,000 cars (one of many) addressed this problem. But the real trouble was overheating. Coolant recovery tanks were not factory-installed until 1974, and if much coolant escaped from the scant six-quart system, the engine could overheat, warping the head or worse—softening the aluminum cylinder surfaces. Brittle valve seals were another engine weakness that could lead to coolant loss or oil consumption. The aluminum block technology itself was sound, and is still in use today.

But in 1970, the press wasn’t privy to any of this. We were learning about innovations aimed at improving quality and reducing cost, like a highly modular body shop boasting 95-percent robotic welding and an assembly line that could theoretically produce 140 cars per hour, though 100/hour was the typical max. A special DuPont nonaqueous-dispersion lacquer paint was hastily developed to accelerate the paint-shop line speed from 85 to 106/hour. To reduce shipping costs, special Vert-A-Pac rail cars were developed to carry 30 Vegas vertically, nose down (the typical roll-on design held 18).

Vegas were available from the outset in hatchback coupe, two-door sedan, wagon, and, single-seat panel delivery van body styles (a passenger seat was optional) with engine outputs of 90 or 110 horsepower. A Wankel rotary engine was highly anticipated for 1974, and a 4WD wagon prototype was even built. In size, the Vega fell smack-dab between Ford’s Pinto and Maverick, which is to say, way larger, heavier, and pricier than Roche’s original Beetle-inspired target. The $2091 base price topped the Beetle’s by $311 and the Pinto’s by $172, so Chevrolet spun it as a more American, upscale car. And let’s face it, the car looked hot. So can you blame us for falling hook, line, and sinker for the Vega and naming it 1971’s Car of the Year? First impressions were rosy. Its 52/48-percent front/rear weight distribution, four-link coil-sprung rear axle, and standard disc/drum brake setup helped deliver class-leading chassis dynamics while long-legged gearing and strong torque gave Vega an edge in highway cruising—never an import strength. Sad to say, all the kudos and positive press proved for naught when the Lordstown, Ohio, plant went on strike shortly after the September 10 launch, depriving dealers of adequate stock until January 1971.

While that strike gave the Pinto a leg up early in the sales race, a 1971 strike at Britain’s Kent engine plant allowed the Vega to play catch-up. The Gremlin had gotten a healthy head start, but faced criticism of shoddy build quality in early press reviews and annual sales averaged one-third of the Pinto’s. As extended-use reports on the Pinto and Vega started appearing, the news wasn’t any better. One magazine’s 2.0-liter Pinto camshaft was installed 10 degrees out of spec. Persistent rough operation of a Vega long-termer earned an engine swap. Rust-proofing shortcuts and a lack of front-fender liners meant perforation often appeared long before the last payment was made. Product improvements and longer warranties helped, but while the imports’ market share leveled off at 15 percent through 1974, overall import sales continued to rise through the ’70s. 1973 proved the best sales year for our trio, when the perennial sales-leading Pinto finally outsold VW.

The Vega and Gremlin names departed after 1977 and 1978, but Ford produced the Pinto through 1980 despite a firestorm of nasty press over its alleged propensity to explode upon rear impact. Some 1.5 million ’71-’75 Pintos were recalled, and a leaked memo suggesting that lawsuit settlements would be cheaper than instituting an $11 design revision on each car helped land Ford in criminal court for reckless homicide (a first), but the company was cleared in March 1980. NHTSA ultimately registered 27 related deaths among the roughly three million Pintos registered.

To size up these Yankee subcompact pioneers, we gathered three of the nicest examples extant. Our 1973 Vega GT is a rare Millionth Vega edition, of which 6500 were built (one for each dealer); all were painted orange with white stripes. It was first titled in 1996, with 80 miles on the odometer. The two registered owners have since accumulated just under 6000 miles, and it’s spent only one night outdoors (after our rainy photo shoot). Our nearly new 1972 Pinto Runabout 2.0L spent most of its life in a museum and now shows just 9800 miles. That makes our 1971 Gremlin X the road-warrior of this trio, having covered 120,000 miles, before being freshened to like-new condition.

If foreign-ness was deemed a virtue in fending off the Germans and Japanese, the Gremlin may have held the advantage. Full aft, the driver’s seat remains way too far forward to accommodate my 32-inseam legs, and the brake pedal towers above the accelerator forcing an Italianate knees-akimbo driving position. Backseat riders must also splay their knees, but the low cushion leaves ample headroom, and visibility is great. The big six loafs effortlessly up to speed and the power steering affords pinky-light control. Vacuum wipers are a quaint curiosity, requiring a momentary throttle lift for nearly every wipe.

Our pristine Pinto starts easily and idles smoothly. The little four-speed stick snicks through the gears with remarkable mechanical precision, though the spacing between the 1-2 and 3-4 gates feels extra wide. A large steering wheel makes easy work of the manual steering, and brake feel is best of the three, with a nice high, firm pedal. Ride quality is vintage flinty from the original-style bias-ply tires and leaf-sprung rear suspension, but the 500-plus pound weight difference relative to the Gremlin gives this Ford a friskier feeling. One annoying safety feature: The ignition release to remove the key is on the left side of the column.

Settling into the Vega’s swankier interior, with its low bucket seat, small-diameter steering wheel, and rally gauge pack, I fire up the big four and notch the similarly precise Saginaw four-speed into gear. The ride on factory-original bias-ply tires is similarly abrupt, but the all-coil suspension feels a bit more sophisticated and the bodywork noticeably narrower. Performance seems on par with the Pinto’s, despite the extra 200 pounds, and the power steering is nicely weighted, requiring far fewer turns than the Pinto’s. After a few gentle miles, I begin to understand how this car won its awards and comparison tests.

So at the end of the day, the Gremlin is the musclecar of the group and probably the car most likely to go 200,000 miles reliably. History suggests the Pinto was the better car, outselling the Vega every year and surviving in far greater numbers today. But emotionally, Jim Brokaw summed it up in January 1972: “Gremlin has power, but Pinto has the price, and a much quieter ride. Which car is best? Vega.”

1971 AMC Gremlin X: Ask the Man Who Owns One

Rick Donathan spends his days hauling Wal-Mart merchandise from Maine to Connecticut and his nights and weekends tending to his burgeoning brood of (primarily) Gremlins and AMXs.

Why I like it: “I got hooked on AMCs in 1977, working for Rogers AMC in Albemarle, North Carolina, in sales, and while the AMX is more desirable and collectible, the Gremlin is unique and different.”

Why it’s collectible: It’s the most muscular of the subcompacts. They’re still way more affordable than true musclecars, and Gremlins are starting to draw greater attention in collector circles.

Restoring/Maintaining: Drivetrain/suspension parts are available, but Chrysler’s purchase of AMC resulted in destruction of most original molds, making body/interior parts difficult to find.

Beware: The later VW/Audi-sourced four-cylinder versions. That engine was woefully underpowered, but the I-6s and V-8s were sturdy and dependable.

Expect to pay: Concours-ready: $4125; solid driver: $1800; tired runner: $850

Join the Club: American Motors Owners Club (amo.com), GremlinX.com

Our Take

Then: “The suspension is firm, the steering quick, the performance zippy. I have the feeling the Gremlin will do well in the hurly-burly of the marketplace. After all, it’s cute, it’s fun, and it’s American.”—A.B. Shuman, Motor Trend, April 1970

Now: This shape still looks as quirky as it did in 1970, eliciting big smiles at shows and cruise-ins. The big, sturdy, understressed engines make the Gremlin a compelling choice for hobbyists interested in road-tripping in their old-timers.

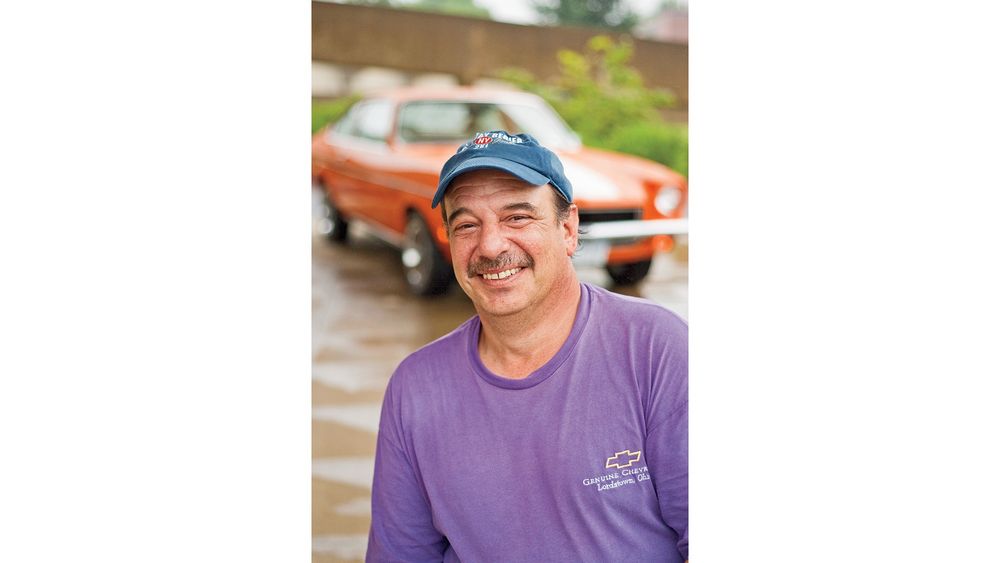

1973 Chevrolet Vega GT: Ask the Man Who Owns One

Robert Spinello has sold Chevys for 30 years, but became smitten with the Vega at age 10, instilling a lifelong passion that has led to ownership of 18 Vegas.

Why I like it: “I fell in love with the orange Millionth Vega at age 14 and later tracked one down as my first car. I love how the suspension, weight distribution, and neutral steering give the Vega world-class handling.”

Why it’s collectible: Engine troubles and rust have claimed so many of these attractive sporty coupes that Cosworths and standard cars command similar money today.

Restoring/Maintaining: All regular wear and replacement parts are still readily available, but trim and body bits are scarce.

Beware: Cooling system deficiencies. Even mild overheating can result in head-gasket failure. And never undertake restoration of a rough Vega with hopes of recouping your investment.

Expect to pay: Concours-ready: $9500; solid driver: $4000; tired runner: $900

Join the Club: Cosworth Vega Association (cosworthvega.com), H-Body.org, Vintage Chevrolet Club of America (vcca.org)

Our Take

Then: “So the Vega 2300 is Motor Trend’s 1971 Car of the Year by way of engineering excellence, packaging, styling, and timeliness. For the money, no other American car can deliver more.” —The editors, Motor Trend, February 1971

Now: Surviving Vegas are like a fossil record of everything that was wrong with the American auto industry circa 1970, but well-maintained examples are also great looking, nice-driving, economical classics—like Baltic Ave. with a Hotel, the best ones can be had for $10K or less.

1972 Ford Pinto: Ask the Man Who Owns One

Phil Reynders splits his time between a welding supply company and Mack’s Antique Auto, a restoration parts business, which gets him entrée to many car shows and swap meets.

Why I like it: “I learned to drive on my ’74 Pinto, which my dad had to drive home from the dealer because I couldn’t drive a stick. I spent an hour or so learning and have been a Pinto fanatic since.”

Why it’s collectible: It’s the poor man’s Mustang and you just don’t see them. They rotted from the ground up, and many of the survivors have been hot rodded. They’re fun little cars that are easy to work on and get lots of stares and thumbs-up.

Restoring/Maintaining: Fairly straightforward. Everything but the badging and brightwork is plentiful. Interior parts can be tough, but are fairly easy to replicate.

Beware: Rear-end crash explosions—check for factory recall filler-neck retrofit kit which included a chrome gas cap replacement (this car retained its original cap, but has the safety retrofits).

Expect to pay: Concours-ready: $9000; solid driver: $2550; tired runner: $625

Join the Club: Pinto Car Club of America (fordpinto.com), turbopinto.com

Our Take

Then: “The Pinto is basic transportation with a vengeance. It’s the 1973 Model A, designed to take you from here to there and back again forever and ever.”—John Pashdag and Wally Wyss, Motor Trend, April 1973

Now: The car that “nobody loved but everybody bought” is quite lovable today, offering nimble performance and respectable economy and interior packaging—especially with the hatch.

I started critiquing cars at age 5 by bumming rides home from church in other parishioners’ new cars. At 16 I started running parts for an Oldsmobile dealership and got hooked on the car biz. Engineering seemed the best way to make a living in it, so with two mechanical engineering degrees I joined Chrysler to work on the Neon, LH cars, and 2nd-gen minivans. Then a friend mentioned an opening for a technical editor at another car magazine, and I did the car-biz equivalent of running off to join the circus. I loved that job too until the phone rang again with what turned out to be an even better opportunity with Motor Trend. It’s nearly impossible to imagine an even better job, but I still answer the phone…

Read More