Why Public EV Charging Sucks … and What’s Being Done to Fix It

Charging’s been a pain for early electric vehicle adopters, but new regulations and initiatives may help before EVs go mainstream.

Charging’s been a pain for early electric vehicle adopters, but new regulations and initiatives may help before EVs go mainstream.

0:00 / 0:00

Imagine frantically searching for a gas station with your refueling light aglow, and when you finally locate one of the few in the area, you pull up to find that every pump but one is out of operation. Even worse, someone’s refueling at the only one that’s working, and you have no idea how long they’re going to take. Then, when it’s your turn, the credit card reader isn’t working, and there’s no attendant available, so you’re forced to call an 800 number and give up your card information to an operator before you can start refueling.

Not a Made-up Scenario

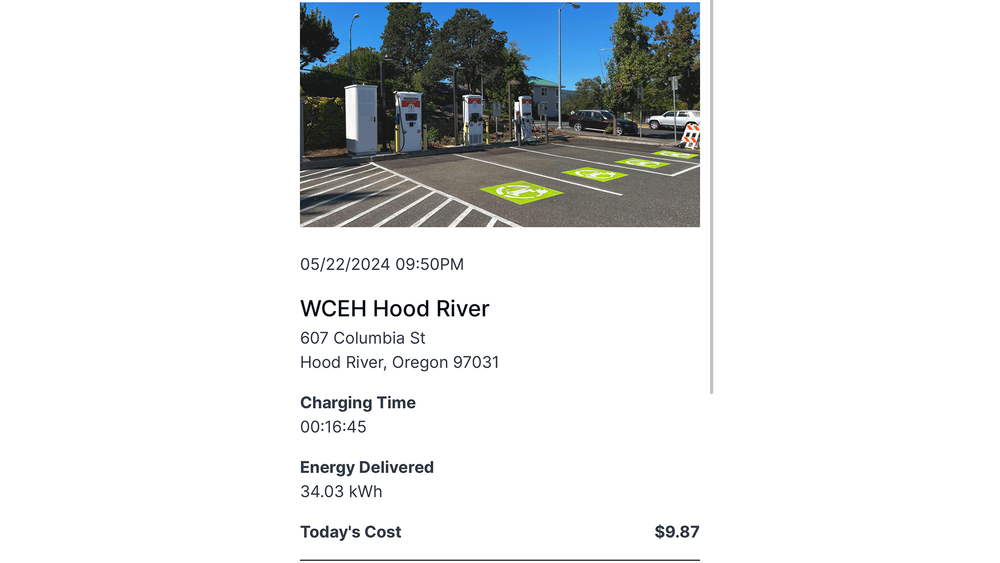

This is what it can be like driving an EV and “refueling” at public charging stations—and it’s not a made-up scenario. It’s one I personally faced last year while behind the wheel of a Mercedes-Benz EQS 500 sedan that desperately needed a charge. It happened again a few weeks later at the same EVCS DC fast-charging station—and the broken chargers and card reader still hadn’t been fixed.

Recent research by the Harvard Business School, which analyzed more than 1 million public EV charging station customer reviews using customized AI models, found that charging stations in the U.S. have an average reliability score of 78 percent. This means that about one in five chargers doesn’t work, and on average, EV chargers are much less reliable than gas stations, said Omar Asensio, a climate fellow at Harvard’s Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society, who led the study.

“Imagine if you go to a traditional gas station and two out of 10 times the pumps are out of order,” Asensio said in a post detailing the results of the study. “I couldn’t even convince my mother to buy an EV recently. Her decision wasn’t about the price. She said charging isn’t convenient enough yet to justify learning an entirely new way of driving.”

In addition, Here Technologies, which provides navigation mapping software for automakers and collects real-time data from EV chargers, stated that more than 4,500 chargers were out over a single week period in late 2023, though the number is likely higher because some inoperable chargers can’t report outages.

Even at EV chargers that are operational, it’s common to encounter frustrating issues such as false starts, payment declines, and charging sessions that are inexplicably cut short. Earlier this year, J.D. Power’s 2024 U.S. Electric Vehicle Experience Ownership Study reported that some 18 percent of public charging attempts failed in the last quarter of 2023 (down slightly from 21 percent over the previous nine months), numbers that largely back up the Harvard study’s results. But among mass-market EV owners, satisfaction with public charger availability was 32 points lower in J.D. Power’s metrics than the period prior.

It all adds up to what’s become a simmering rage among EV early adopters who use (non-Tesla Supercharger) public chargers. The issues are myriad, among them: charger and EV incompatibility, a rush to install chargers without planning for proper maintenance, and a lack of experienced personnel to fix broken chargers. It’s why some consumers have been reluctant to buy EVs, especially those who live in a multiunit dwelling and don’t have access to home charging.

Discrepancies in Protocols

A prime driver of problems with public charging are discrepancies in software and communication protocols between chargers and EVs, said John Smart, director of national charging experience for the ChargeX consortium at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL). ChargeX, a joint effort led by three national laboratories that are funded by the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, brings together EV industry stakeholders to rapidly measure and improve public charging reliability and usability.

EV charging is a complex process, and problems usually arise when each party doesn’t implement charging standards in the same way, Smart said. “There are a lot of potential points of integration that if not done well can lead to failure,” he said. Chargers go through several steps to initiate a charging session, and if one step fails, the charge can’t start. It could be that the car and charger aren’t speaking the same language, or one doesn’t respond fast enough, and it leads to a timeout. Other issues that can disrupt a charging session range from a loss of cloud connectivity to a recent software update on an EV.

One of the bigger present concerns Smart pointed out is the lack of standard error codes for EV charging. While the codes do exist, they're still largely unique to each company, complicating the process and leading to confusion and disruption. “It’s not like where we've become accustomed to standard diagnostic codes in cars that trigger a check-engine light,” Smart said.

The ChargeX consortium participants also perform inoperability testing between chargers, vehicles, and backend providers. “Automakers provide vehicles and charging companies provide chargers to test and ensure that every charger communicates correctly with every vehicle,” Smart said. “They don't need the Rosetta Stone to interpret the problem, quickly identify the root cause, and fix it.”

Not Enough Technicians

Even in a perfect world where a more streamlined communication process between car and charger and unified error-code standards have been ironed out, based on the number of broken chargers today, there still aren’t enough technicians to fix them now or in the future when something goes wrong. Qmerit, which provides EV charging installation services and has approximately 4,000 network locations in the U.S. and Canada serviced by 25,000 electricians, predicts that by 2030 about 142,000 certified technicians will be needed to build and maintain public EV charging stations. Filling these positions will be a challenge, said Tom Bowen, president of Qmerit Solutions, the division of the company that focuses on commercial and public charging.

“If you look at the number of electricians today, it's down by about 50 percent from 20 years ago, and there are more electricians retiring out of the workforce than are entering it,” Bowen said. “Scarcity of labor will have a big impact if we’re to meet the EV adoption levels proposed, so a key focus for Qmerit and others in the space is workforce development. We’re helping develop skills, recruit electricians, and train and certify them to ensure that they're adequately prepared.”

Industry stakeholders, including charging equipment servicers like Qmerit, automakers, utility companies, educational institutions, and others, work with the nonprofit Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Training Program (EVITP) to recruit and educate charging station technicians. EVITP provides an Electric Fast Track career path with partners such as the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) and the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA). In February EVITP and several partners began providing training and certification for qualified electricians and outreach to potential recruits through an EV-related curriculum developed by SkillFusion.

“We’re creating a work-ready database of technicians with a variety of skillsets to address key issues and roadblocks toward EV adoption,” Rue Phillips, president and co-founder of SkillFusion, said. “We want to reach out as much as possible and particularly to under-privileged communities.”

Charge Station Companies Not Held Accountable

The issue of unrepaired chargers largely grew out of a gold-rush mentality to stake claims as the EV-charging business began to boom and funds flowed freely from legal settlements, public coffers, and investors. Two the largest companies in the charging space grew out of scandal—Electrify America is funded by penalties imposed on Volkswagen for its Dieselgate scandal, and EVgo was created as part of a settlement following the Enron scandal—while EVgo and major player ChargePoint went public through special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) deals in 2021.

Making matters worse, operators haven’t exactly been held to account when their chargers break down or are otherwise compromised. The problem has been particularly acute with Electrify America, which has been at the bottom of surveys and the subject of automaker ire. In general, despite some improvement, the state of the charging industry outside of Tesla and its Supercharger network has been uneven at best, and early EV adopters have paid the price, souring many on the EV ownership experience.

“The mid-investment phase in the U.S. was driven by cash-rich IPO/SPAC-IPOs companies and dominated by land-grab strategies,” Michael Winter said. He’s the CEO of Jolt Energy North America, a European company he co-founded that operates DC fast chargers that work with low-voltage power grids and battery storage systems to allow EVs to reach up to 150 miles of range in about 10 minutes depending on the vehicle. “The early goal of those companies was to get chargers in the ground without consideration for location and serviceability.”

Real estate developers and other site owners eager for the opportunity to become EV fast-charging operators bought equipment without having the expertise to maintain it, Winter added. “It was more of a ship-and-forget mindset than a full lifecycle mindset that got the industry in trouble,” he said. “The term Wild West comes to mind, and it hurt the industry. Equipment uptime, preventative maintenance, and managing the value chain of EV charging is really hard.”

Adding to the chaos, many of the initial charging networks were funded by states and the federal government as well as local electric utilities—each often working under their own timetables. “Companies who were awarded funding were held to aggressive timelines, and in many cases the programs prioritized installation of chargers but not operation and maintenance,” Smart said. “Chargers were not repaired, and the funding sponsor did not hold companies accountable.”

To help smooth out the rough spots, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), passed in 2021, made $7.5 billion available to build 500,000 public chargers by 2030, with $5 billion of that earmarked to create a “backbone” of high-speed chargers at least every 50 miles along major U.S. roadways. The money will come with a maintenance string attached: IIJA’s National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program stipulates that federally funded charging stations must have an average annual uptime exceeding 97 percent.

“To my knowledge, it’s the first time there’s been a reliability-focused requirement in these types of programs,” Smart said. “And there are other requirements that give me a lot of comfort as a taxpayer that the public dollars will go toward not only installing chargers but ensuring that they’re reliable for years to come.”

Under the IIJA, each state is responsible for administering how the federal dollars are allocated, Qmerit’s Bowen said. So far, things have been more than a bit rocky out of the gate as far as he’s concerned. “The process is very cumbersome and time consuming,” he said. “That’s been a source of frustration for individuals that hear about funds coming in but don't necessarily see an improvement in public charging.”

Steps in Place to Solve Charging Issues

While it’s all currently of little comfort to EV drivers who experience an inordinately high number of fails at public charging stations, multiple efforts are underway to help make public charging more reliable. Many automakers in the U.S. are adopting what's known as the North American Charging Standard (NACS) to take advantage of Tesla’s more extensive and reliable Supercharger network. Although a recent layoff of executives and staff members effectively gutted the company's Supercharger team, it remains the gold standard among charging networks, with a vast number of high-speed DC chargers available nationwide.

Additionally, BMW, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Mercedes-Benz, and Stellantis have formed a joint venture called Ionna. It’s being billed as a public charging service to better support what the brands hope will be millions of their future EVs. Its goal is to build a network of at least 30,000 DC fast chargers that, Ionna said in a statement, “will be in convenient locations offering canopies wherever possible and amenities such as restrooms, food service, and retail operations.” Ionna plans to support NACS and the Connected Charging System standard as well as Plug & Charge billing capabilities, and it says some sites will be staffed with full-time personnel to help with driver problems and questions. Ionna has also suggested it may own some of its charging locations instead of leasing sites, as most other charging networks do now, allowing it to choose where the chargers are placed and to better supervise maintenance.

After receiving regulatory approval, Ionna began operations in February and plans to launch its network later this year. On June 11, the organization announced it is establishing what it calls a central Quarterback Lab at its headquarters in Durham, North Carolina, as well as seven satellite labs in conjunction with its member automakers. Ionna said in a statement that the labs will conduct compatibility tests on EVs to “set new standards and benchmarks in the industry.”

The ChargeX consortium is also performing inoperability testing between chargers, vehicles, and backend providers. “Automakers provide vehicles and charging companies provide chargers to our labs to test and ensure that every charger communicates correctly with every vehicle,” Smart said. “I work with hundreds of members of ChargeX, and they’re 100 percent dedicated to improving the customer experience and reliability. The industry realizes that to be successful, they need to prioritize that.”

Not a Gas Station

Despite the obvious correlation between traditional gas and EV charging stations (the “pumps” and today’s general infrastructure look similar in several ways on the surface), Smart largely considers it an inaccurate analogy. “There's so much more technology involved with charging than there is with gas pumps,” he said. “They use completely different technologies, and a gas pump is almost exclusively mechanical. With public charging, and particularly fast charging, there’s not only the mechanical interface that needs to be safe to avoid hazards with high-powered electricity but complex communication between the car, the charger, and the cloud.”

Adding to all the technological and mechanical complexity has been the challenges around building an infrastructure on the fly with multiple players involved in an attempt to replicate what the petroleum industry has been honing for more than a century. “It takes time to learn how to design, build, and maintain successful EV charging stations,” Smart said. “The EV charging industry is trying to do in two decades what the gas fuel industry has done for more than 100 years.”

Part of that on-the-fly approach has been keeping up with the ever-improving charging technology, with several companies replacing increasingly outdated first- and even second-generation chargers with newer, more reliable models with better diagnostics (being able to report if a cord has been cut, for instance) designed to service a wider variety of EVs, Smart said. And given the ever-growing competition in the space, companies are working to differentiate themselves by doing a better job of maintaining the chargers and keeping them operational.

Despite the challenges today’s EV drivers have been experiencing at times—and all the disruption rapid technological changes can bring—experts like Smart believe things are improving and will continue to do so. “I’m highly optimistic that the U.S. EV charging system is moving in the right direction,” he said.